Nothing is more delightful than the sound of a waterfall in the spring. The Nature Preserve has several waterfalls and natural springs that flow when it rains. Unfortunately, our waterfall on Little Huckleberry Creek tends to slow to a mere trickle during the dry summer months.

Other waterfalls with a more reliable source, such at Cumberland Falls on the Cumberland River, will roar down a 60 foot high drop all year long. As the waterfall recedes, it leaves a gorge and large boulders in the water downstream.

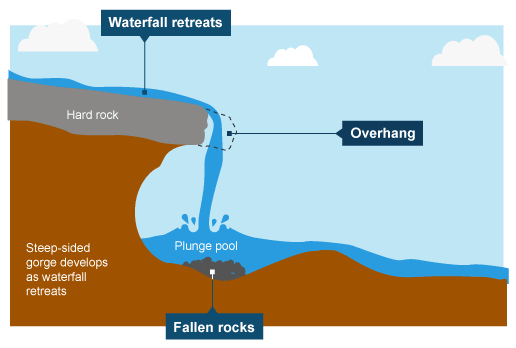

Water is one of the most powerful shapers of our world, and waterfalls are great examples of hydraulics in action. Cumberland Falls probably started about 45 miles downstream from its present location. Water always flows from high to low, eroding the earth as it flows. That’s the easy part. Then why don’t we have more waterfalls? It depends on the rock under the river. A hard layer erodes more slowly than a layer of softer rock. For example, limestone is harder than sandstone. So the underlying sandstone layer will erode, and the upper layer of limestone will come crashing down when there is nothing to support it. You can see this process even in a small seasonal waterfall such as ours.

Yahoo Falls is the highest waterfall in Kentucky at 113 feet, and is located in McCreary County, not too far from Cumberland Falls. The stream is small, but over the millennia it has carved out a huge overhang allowing visitors to walk behind the falling stream. Native Americans sometimes used it for shelter, and hikers still run under the rocks when caught in a sudden rainstorm. Rough-winged Swallows nest in the safety of the shelter too, zooming in and out of the crevasses. We think rocks are the hardest things around, but with persistence and lots of time, water is always the winner!