Have you heard a strange, ethereal sound overhead in the last few days? Run outside, and you may be fortunate to see Sandhill Cranes on the move migrating over Kentucky, back to their northern breeding grounds. The Sandhill Crane takes its name from a particularly beautiful region in the broad sweep of grassland at the heart of North America. In central Nebraska, sand dunes created during the Ice Age have been stabilized by deep-rooted prairie plants including sand bluestem, evening primrose, leadplant, and hundreds of unique species of wildflowers and grasses. These Sand Hills ripple northward from the banks of the Platte River—characterized as “a mile wide and an inch deep” by settlers headed west on the Oregon trail—where shifting shallow channels, wetlands, and sandbars host the planet’s largest gathering of cranes each spring. Up to a half-million birds replenish their reserves as they pause here on their migration to wetlands further north in the Dakotas, Minnesota, and Canada.

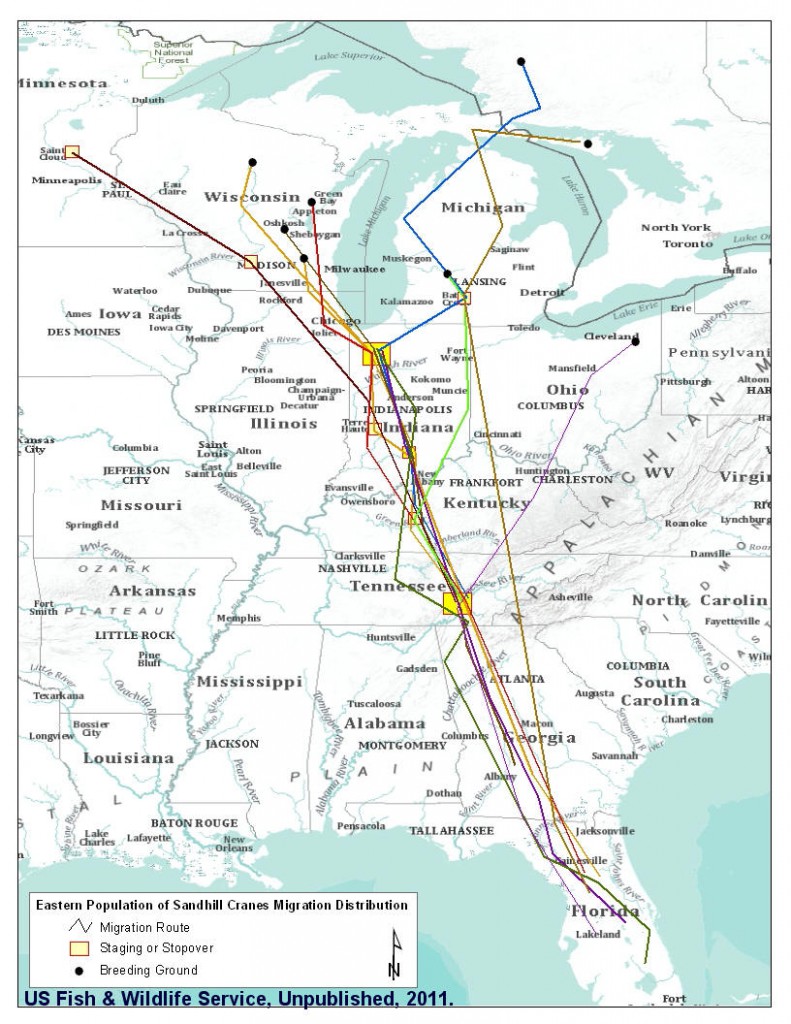

The Eastern Population of Sandhill Cranes is rapidly expanding in size and geographic range. The core of their breeding range is in Wisconsin, Michigan, and southern Ontario; however, their range has expanded in all directions as the population has grown. Little is known about the geographic extent of breeding, migration, and wintering ranges of Eastern Population cranes, or migration chronology and use of staging areas. Between 2009 and 2012, Global Positioning System satellite Platform Transmitting Terminals were attached to 30 Sandhill Cranes to assess their movements throughout the year. Cranes were tagged at refuges in Indiana, Minnesota, Tennessee and Wisconsin. Hiwassee Wildlife Refuge near Chattanooga, TN, is a large staging area, as is Jasper-Pulaski in northern Indiana. As you see from this map, the migration route also flies over Kentucky, including Louisville!

Sandhill Cranes are very large, tall birds with a long neck, long legs, and very broad wings. The bulky body tapers into a slender neck; the short tail is covered by drooping feathers that form a “bustle.” The head is small and the bill is straight and longer than the head. These are slate gray birds, often with a rusty wash on the upperparts. Adults have a pale cheek and red skin on the crown. Their legs are black. Juveniles are gray and rusty brown, without the pale cheek or red crown.

Wetlands are vital to Sandhill Cranes—sedge meadows, marshes, and other wetlands are where the cranes build their nests and defend their eggs and young from predators. They are also important food sources across the full range of their migrations. The Sandhill Crane is not exceptional in its need for wetlands. It may be no surprise that areas with plentiful wetlands host a variety of creatures that have made themselves at home in the marshes, bogs, and fens, that cover much of the landscape, but many creatures of drier landscapes also depend on green oases in a dry land. As wetlands have been drained to make room for urban and agricultural expansion, the continued existence of their unique plant and animal communities is threatened, along with critical services—like soaking up flood waters, buffering coasts from storms, filtering water—that benefit people and land.

This week Cranes in a local Kentucky resting spot totaled anywhere from 10,000 – 22,000 birds, gazing in the corn stubble of muddy fields. Although some start breeding at two years of age, Sandhill Cranes may reach the age of seven before breeding. They mate for life—which can mean two decades or more—and stay with their mates year-round. Juveniles stick close by their parents for 9 or 10 months after hatching.

So the next time you hear “ka-roo” going overhead, run out to say hello to the migrating Sandhill Cranes!