Kentucky’s native grasslands have almost disappeared by the 21st Century, but it is important to restore and protect these areas. Early settlers found vast forests, except in south-central and western Kentucky, where they rode for days on horseback without being able to see over the top of the grass.

|

| Controlled Burn |

The Indians had repeatedly burned the forests that once covered the region as a means to stampede and kill big game. These fires created an open savanna that in turn drew all types of wild game to feed off its lush grasses. Buffalo herds migrated eastward across the Mississippi to Illinois, and then to Kentucky. These herds came to the Barrens and multiplied, providing food and clothing for the Indians. Settlers found the treeless areas easy to cultivate. Originally the pioneers thought the treeless grasslands infertile because of the lack of forestation. They soon found the soil to be some of the best that they had encountered. Farms and communities soon began to cover the area.

|

| Northern Bobwhite |

|

| Big Bluestem and Native Flowers |

Native grass communities provide other environmental benefits, including filtering sediments and chemicals from runoff, dispersing water flow, and reducing erosion. Most native grass species develop a strong root system that contributes to an increase in soil fertility, recycling nutrients while alive and returning vital nutrients to the soil as the roots decompose. They also recover quickly after fire or drought. Because many native grasses are adapted to survive in almost any soil conditions, they require no fertilizer or irrigation after planting. Thus, over the long term, planting native grasses and wildflowers can reduce maintenance costs.

|

| Bobwhite Nest in Grass |

Grassland birds adapted to these areas, and cannot live elsewhere. These birds eat a variety of foods found in the grasses ranging from grass seeds to crickets, grasshoppers and worms; and in the case of grassland raptors, such as the Northern Harrier and Short-eared Owl, small mammals such as meadow voles, small birds, and even small reptiles and amphibians. Grassland birds nest on the ground rather than in trees, using the structure provided by grasses both for the construction of the nest and as cover from predators. Ground nesting behaviour leaves grassland birds vulnerable to disturbances such as mowing or haying during the breeding season. Nest predation and destruction, coupled with loss of habitat, are causing grassland bird populations to drop without a good chance of recovery.

|

| Field Sparrow |

After leaving the nest, and later in the life cycle, grasses provide these birds with cover and protection from prey as they often do not fly from a predator, but run through the grasses to escape danger. Native grasses growing in clumps allow these ground runners to escape through passages between the clumps. This Field Sparrow will perch on a waving grass stem to look around, then drop down into invisibility.

|

| Dickcissel |

Loss of habitat has lead to decline of grasslands bird populations by 60 to 80% in the last 40 years, according to the Audubon Society’s recent list of Top 20 Birds in Decline. Plowing the grasslands for crops, then planting one kind of crop (such as corn) in large areas, creates less diversity, food and shelter. 40 years ago, there were more pastures and fields that birds found acceptable. Since then we have turned farmland into industrial or residential areas, paving over much land entirely, changing and redirecting the amounts of water available.

|

| Invasive Johnson Grass |

Invasive plants take over remaining space, grow faster than native plants, and inhibit the growth of native plants. Native animals do not eat these plants, so they spread even more, and the animals have less to eat. Fragmentation of habitat areas is a factor in the decline as well. Although grassland birds may use very small grasslands (under 40 acres, sometimes even under 10 acres) for foraging or other habitat needs, managing areas of at least 40 acres will provide most habitat needs for a diversity of grassland birds. The grass areas we have now may simply be too small for the birds to successfully breed and raise their young.

|

| Big Bluestem and Goldenrod |

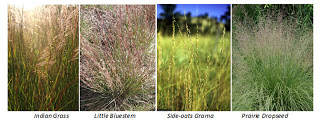

Creasey Mahan is working to restore the native grasslands on the Preserve at Meadowlark Meadow. Grasslands are being planted with native grasses and wildflowers. The primary grasses are prairie grasses, known as “warm season” or “bunch” grasses. All of these grasses provide food and shelter for wildlife, and help retain water in the soil and prevent erosion.

|

| Black-eyed Susans |

Native wildflowers have been added to Meadowlark Meadows to provide food for wildlife and add a scenic quality to the grassland. Primary wildflowers are black-eyed Susan, partridge pea, Illinois bundleflower, common and butterfly milkweeds, purple coneflower and New England aster.

|

| Partridge Pea |

If you build it they will come, or so we hope. By planting native grasses and managing them to control invasives, we hope to encourage these declining birds to live on the Preserve where we can all enjoy them. As you walk across these areas at the Preserve next year, keep your ears open for the song of Eastern Meadowlark, Field Sparrows, and maybe the more rare Dickcissel or Grasshopper Sparrow.